Executive Summary

- SentinelLABS has discovered a novel malware variant of AcidRain, a wiper that rendered Eutelsat KA-SAT modems inoperative in Ukraine and caused additional disruptions throughout Europe at the onset of the Russian invasion.

- The new malware, which we call AcidPour, expands upon AcidRain’s capabilities and destructive potential to now include Linux Unsorted Block Image (UBI) and Device Mapper (DM) logic, better targeting RAID arrays and large storage devices.

- Our analysis confirms the connection between AcidRain and AcidPour, effectively connecting it to threat clusters previously publicly attributed to Russian military intelligence. CERT-UA has also attributed this activity to a Sandworm subcluster.

- Specific targets of AcidPour have yet to be conclusively verified; however, the discovery coincides with the enduring disruption of multiple Ukrainian telecommunication networks, reportedly offline since March 13th.

- The ISP attacks are being publicly claimed by a GRU-operated hacktivist persona via Telegram.

On March 16th, 2024, we identified a suspicious Linux binary uploaded from Ukraine. Initial analysis showed surface similarities with the infamous AcidRain wiper used to disable KA-SAT modems across Europe at the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine (commonly identified by the ‘Viasat hack’ misnomer). Since our initial finding, no similar samples or variants have been detected or publicly reported until now. This new sample is a confirmed variant we refer to as ‘AcidPour’, a wiper with similar and expanded capabilities.

This is a threat to watch. My concern is elevated because this variant is a more powerful AcidRain variant, covering more hardware and operating system types. https://t.co/h0s6pJGuzv

— Rob Joyce (@NSA_CSDirector) March 19, 2024

Our technical analysis suggests that AcidPour’s expanded capabilities would enable it to better disable embedded devices including networking, IoT, large storage (RAIDs), and possibly ICS devices running Linux x86 distributions.

Following our initial reporting on Twitter, CyberScoop reported a claim from the Ukrainian SSCIP attributing our findings to UAC-0165, clustered as a subgroup under the outdated ‘Sandworm’ threat actor construct. We reported our initial findings to partners on Saturday, followed by the public analysis thread on Twitter. Our analysis is ongoing.

AcidRain Context

On February 24th, 2022, a cyber attack rendered Eutelsat KA-SAT modems inoperable in Ukraine. Spillover from this attack rendered 5,800 Enercon wind turbines in Germany unable to communicate for remote monitoring or control and reportedly affected vital services across Europe.

On March 30th, 2022, we identified a wiper component which we dubbed ‘AcidRain’ as a part of the attack chain that caused this disruption by rendering Surfbeam2 modems inoperable in an attempt to disable vital Ukrainian military communications at the start of the Russian invasion.

During our original analysis of AcidRain, we assessed with medium-confidence that there are developmental similarities between AcidRain and a VPNFilter stage 3 destructive plugin named ‘dstr’. In 2018, the FBI and Department of Justice attributed the VPNFilter campaign to the Russian government.

On May 10th, 2022, the European Union and its Member States issued an official condemnation of this activity, holding the Russian government responsible. Despite an abundance of wipers and cyber operations against Ukrainian targets in the subsequent months and years, we had not seen any further uses of AcidRain or similar components.

Enter AcidPour

On March 16th, 2024, we observed a new Linux wiper we are naming ‘AcidPour’. We alerted relevant partners immediately to stem the potential for any additional significant regional impact, followed by public dissemination of technical indicators and early analysis to alert the research community and encourage vigilance and contributions.

Our initial finding centered on surface similarities with AcidRain, so we placed a large emphasis on ascertaining whether a more conclusive relationship could be established between the two components at a technical level, as well as an understanding of its capabilities.

Technical Analysis

Where AcidRain is a Linux wiper compiled for MIPS architecture for compatibility with the devices targeted, AcidPour is compiled for x86 architecture. Despite both targeting Linux systems, the architecture mismatch somewhat limits our ability to compare the compiled codebases.

Notably, AcidRain was a hamfisted wiper rather than a specifically tailored solution. It operates by iterating over all possible devices in hardcoded paths, wiping each, before wiping essential directories. Its lack of specificity suggests a lack of familiarity (or time) to adapt to the specifics of the Surfbeam2 targets. However, that also means that AcidRain can serve as a more generic tool able to disable a wider swath of devices reliant on embedded Linux distributions.

| MD5 | 1bde1e4ecc8a85cffef1cd4e5379aa44 |

| SHA1 | b5de486086eb2579097c141199d13b0838e7b631 |

| SHA256 | 6a8824048417abe156a16455b8e29170f8347312894fde2aabe644c4995d7728 |

| Size | 17,388 bytes |

| Type | ELF 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386, version 1 (SYSV), statically linked, stripped |

| Filename | ‘tmphluyl8zn’ |

| First Submitted | 2024-03-16 14:42:53 UTC, Ukraine |

The AcidPour variant is an ELF binary compiled for x86 (not MIPS), and while it refers to similar devices, the codebase has been modified and expanded to include additional capabilities. Our best automated attempts to compare across different architectures only yields a low confidence < 30% similarity.

We took that as a base measurement and proceeded to conduct a deep-dive analysis of the new binary with a focus on testing the hypothesis that the two are related variants, as well as detailing any net new capabilities.

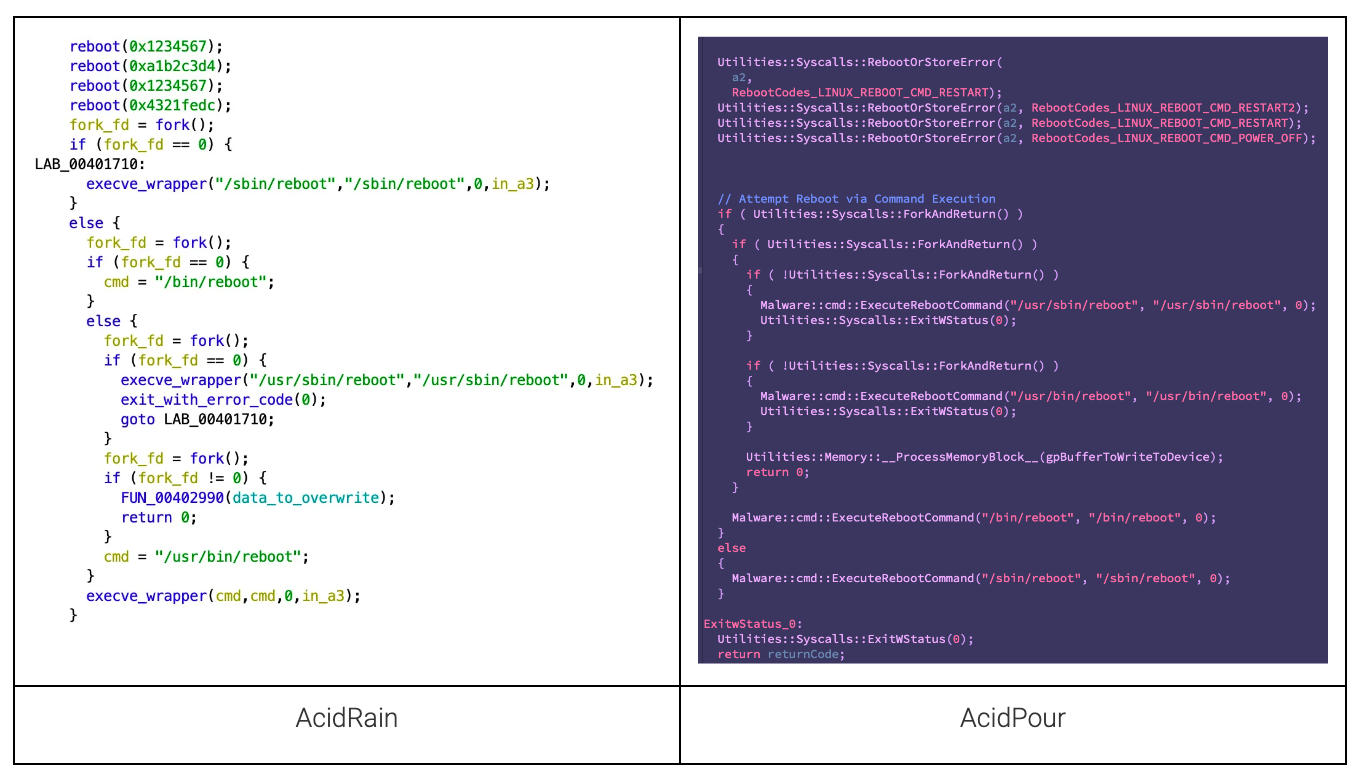

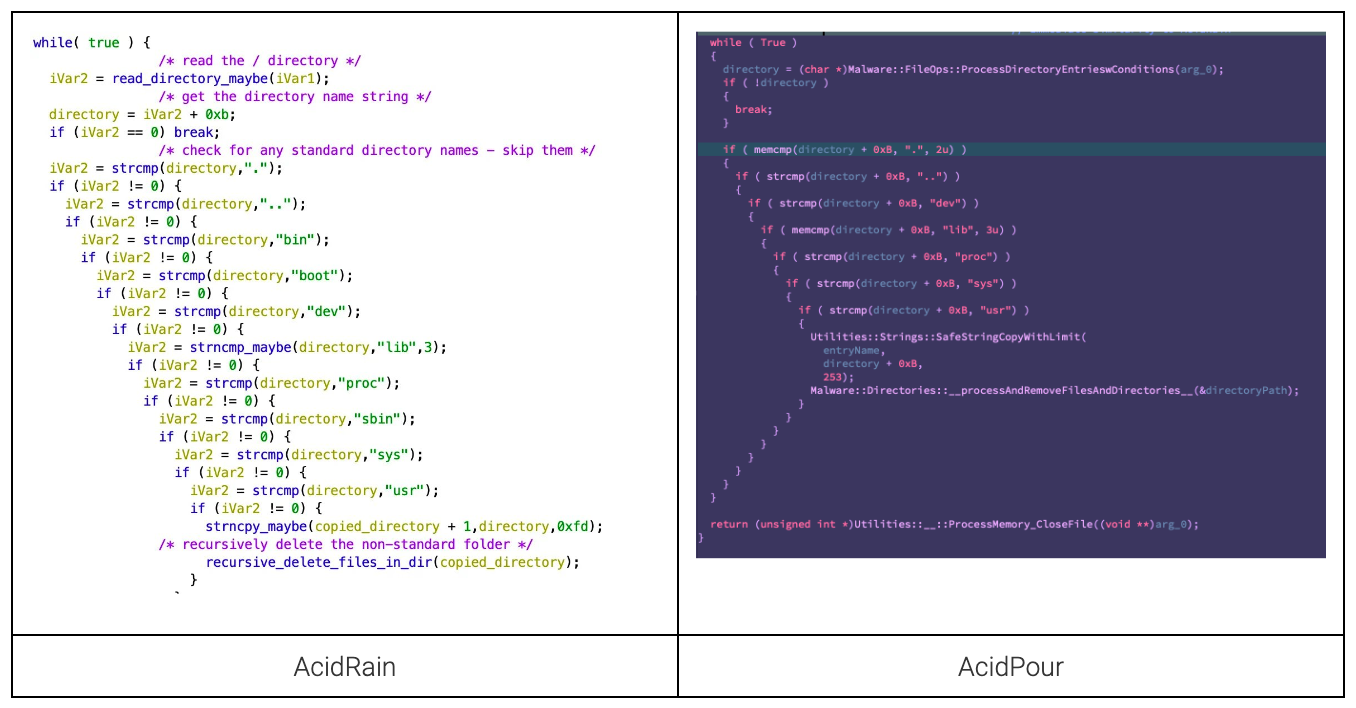

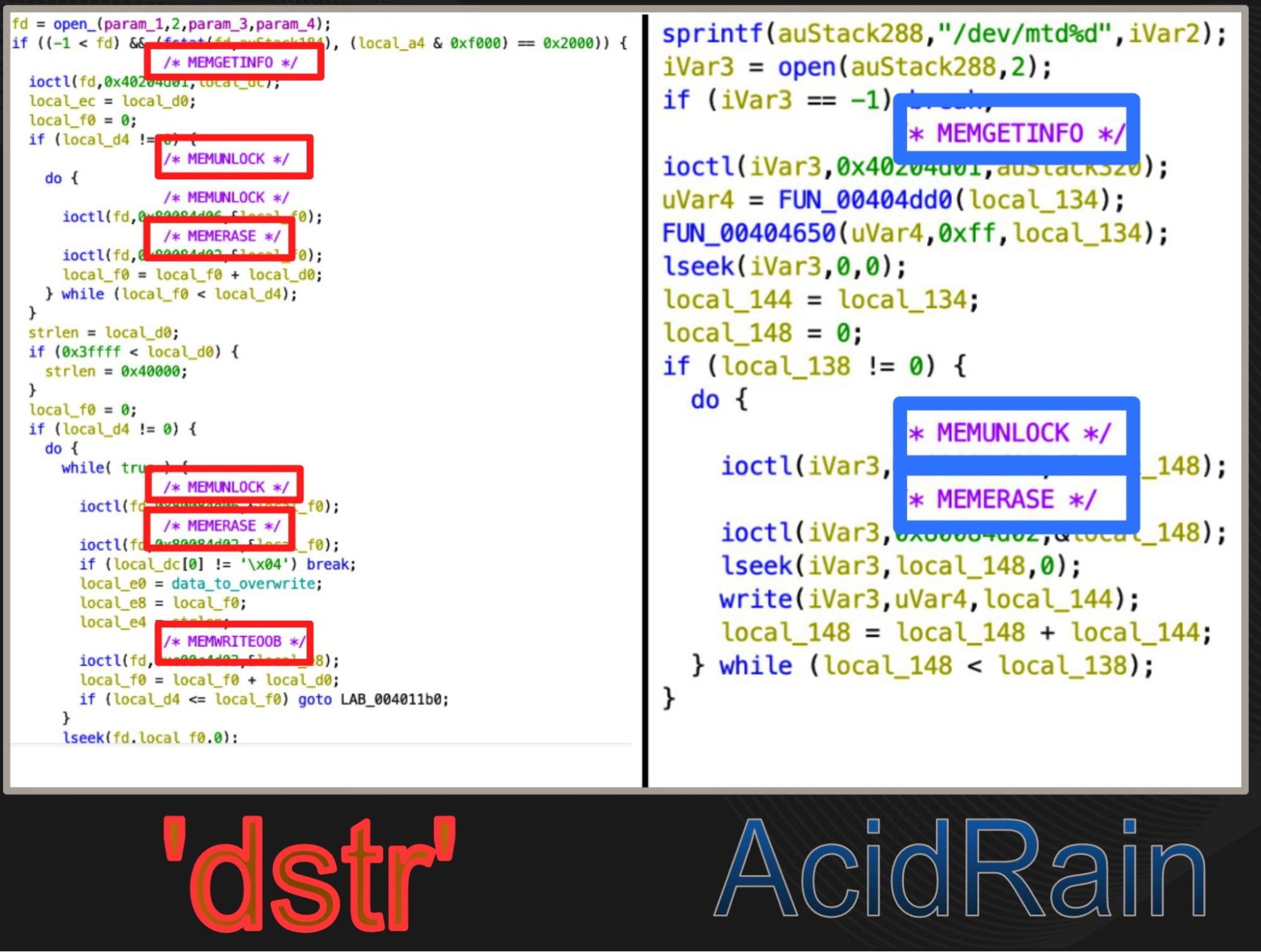

Notable similarities include the use of the same reboot mechanism, the exact logic of the recursive directory wiping, and most importantly the use of the same IOCTL-based wiping mechanism used by both AcidRain and the VPNFilter plugin ‘dstr’.

Shared Reboot Mechanism

Recursive Directory Processing

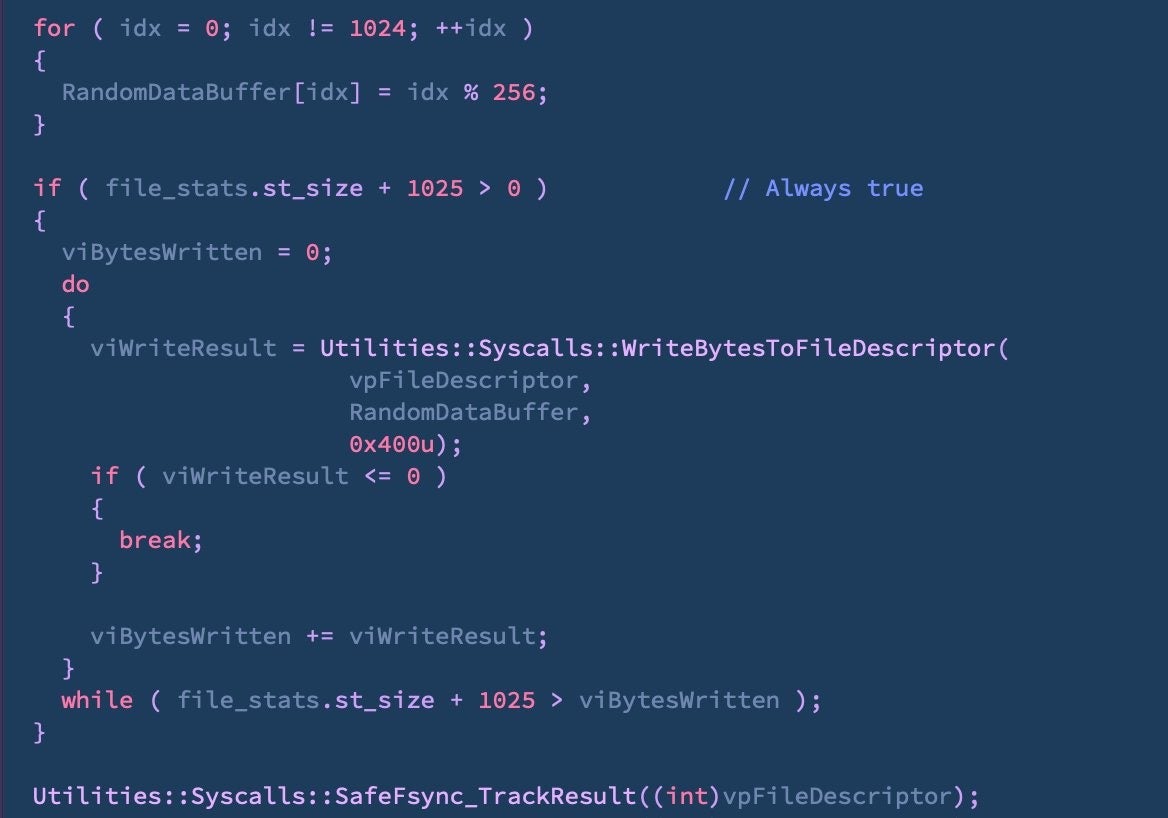

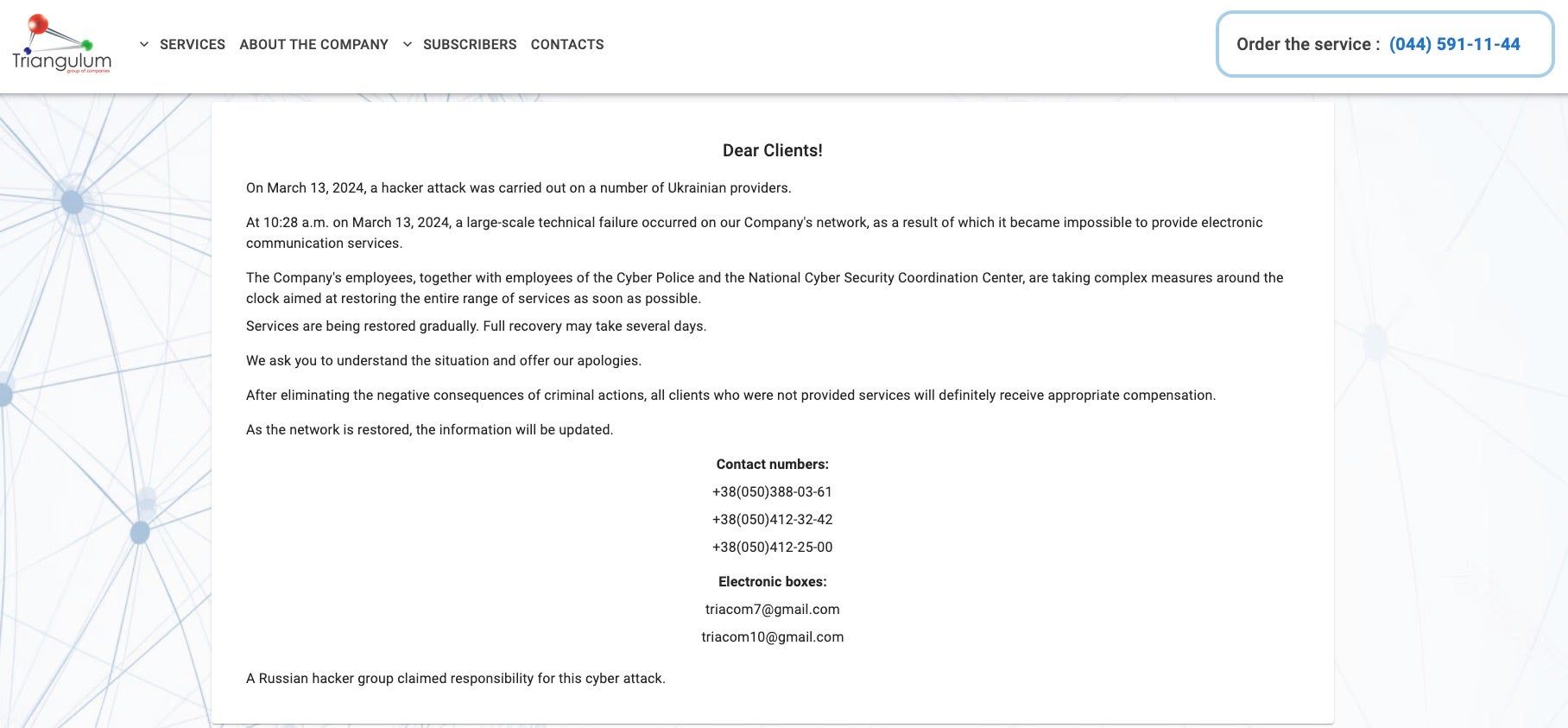

Wiping Mechanisms

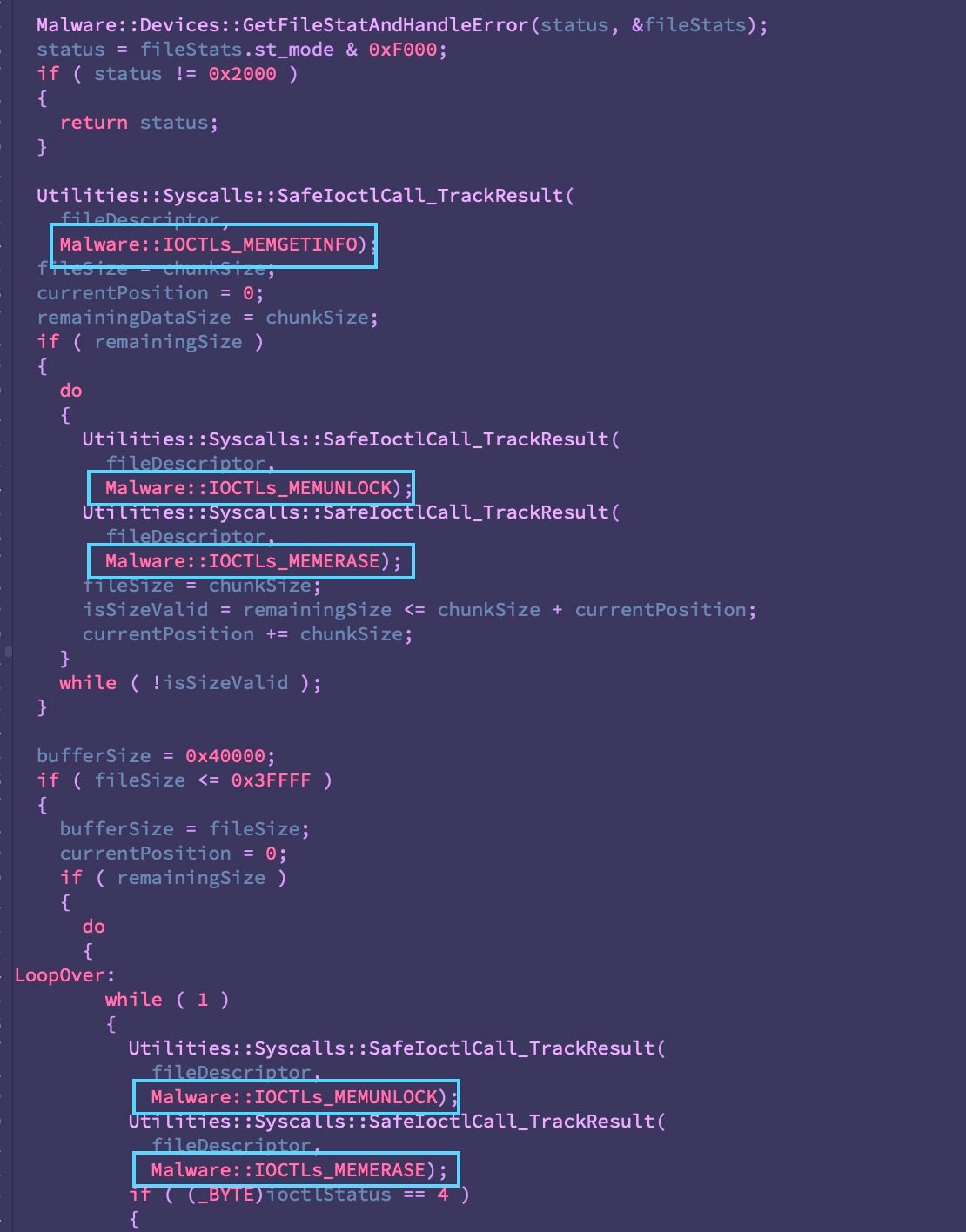

At the time of discovery, we noted the similarities between AcidRain’s IOCTLs-based device-wiping mechanism and the VPNFilter plugin ‘dstr’, pictured below:

AcidPour relies on the same device wiping mechanism:

AcidPour’s Net New Functionality

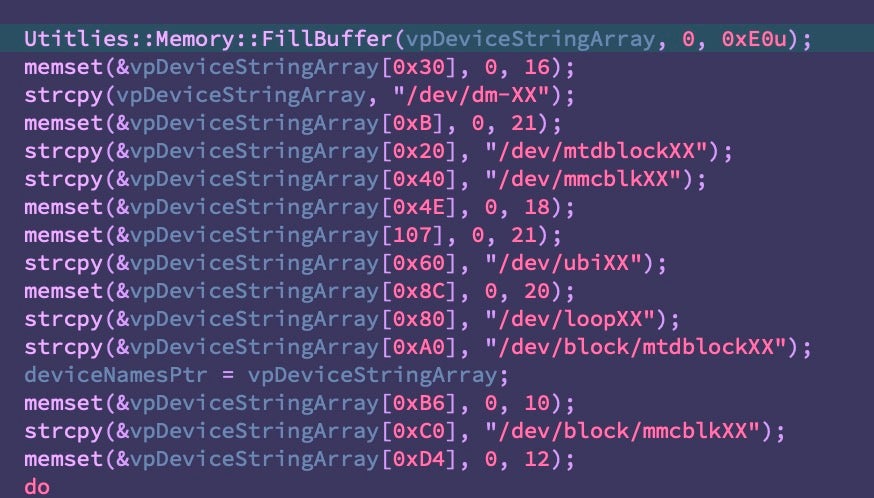

AcidPour expands upon AcidRain’s targeted linux devices to include Unsorted Block Image (UBI) and Device Mapper (DM) logic.

AcidRain’s supported devices:

| /dev/sd* | A generic block device |

| /dev/mtdblock* | Flash memory (common in routers and IoT devices) |

| /dev/block/mtdblock* | Another potential way of accessing flash memory |

| /dev/mtd* | The device file for flash memory that supports fileops |

| /dev/mmcblk* | For SD/MMC cards |

| /dev/block/mmcblk* | Another potential way of accessing SD/MMC cards |

| /dev/loop* | Virtual block devices |

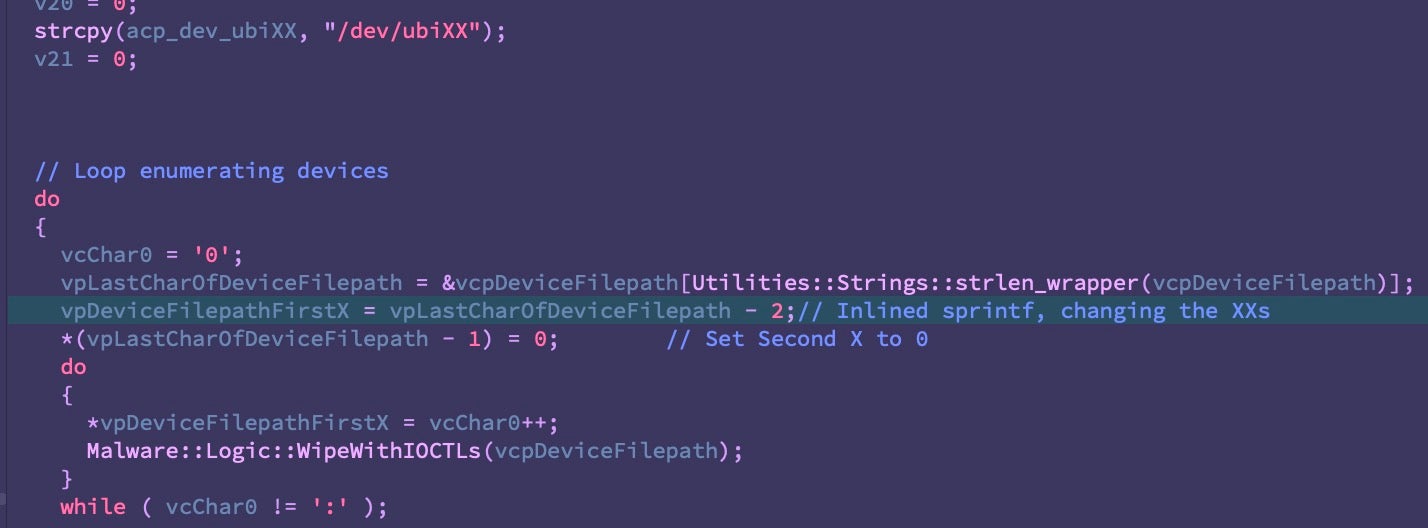

AcidRain targeted flash chips via MTD for raw access to flash memory in the form of /dev/mtdXX device paths. This capability is expanded in AcidPour to include /dev/ubiXX paths. UBI is an interface built on top of MTD to act as a wear-leveling and volume management system for flash memory. These devices are common in embedded systems dependent on flash memory like handhelds, IoT, networking, or in some cases ICS devices.

AcidPour also adds logic for handling /dev/dm-XX paths to access mapped devices. The device mapper framework enables logical volume management (LVM), abstracts physical storage into logical volumes for easier resizing, manipulation, and maintenance.

These devices act as virtual layers of block devices, enabling features like logical volumes, software RAID, and disk encryption. This would put devices like Storage Area Networks (SANs), Network Attached Storage (NASes), and dedicated RAID arrays in scope for AcidPour’s effects.

All Local, No imports

One of the most interesting aspects of AcidPour is its coding style, reminiscent of the pragmatic CaddyWiper broadly utilized against Ukrainian targets alongside notable malware like Industroyer 2.

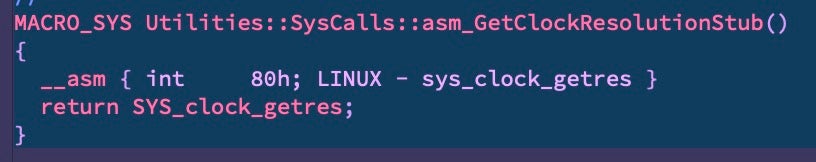

AcidPour is programmed in C without relying on statically-compiled libraries or imports. Most functionality is implemented via direct syscalls, many called through the use of inline assembly and opcodes.

This forces some unusual seemingly-archaic approaches to simple operations like storing and modifying format strings for device paths as needed in the course of their operations.

Self-Delete

Perhaps as a response to the discovery of AcidRain, this new version now kicks off with a self-delete function. It maps the original file into memory, then overwrites it with a sequence of bytes ranging from 0-255 followed by a polite Ok.

Alternate Device Wiping Mechanism

At the time of our discovery of AcidRain, there was some confusion about the involvement of a wiper in taking down the Surfbeam2 modems. As we reverse engineered the malware, we found a second wiping mechanism that didn’t rely on IOCTLs. This alternate mechanism filled a buffer with the highest byte value (0xFFFFFFFF) and proceeded to decrement by 1, overwriting its target with the result. That allowed us to connect AcidRain’s expected output with dumps of the affected devices.

Viasat incident

I managed to dump the flash of two Surfbeam2 modems: 'attacked1.bin' belongs to a targeted modem during the attack, 'fw_fixed.bin' is a clean one.

A destructive attack. pic.twitter.com/0QuTrLFR2A— reversemode (@reversemode) March 31, 2022

With this crucial detail in mind, we were curious as to whether AcidPour implements an analogous alternate wiping mechanism.

Depending on the device type, a different wiping mechanism is engaged, overwriting the device repeatedly with the contents of a 256kb buffer. The specifics of this alternate mechanism require further analysis.

Attribution

Earlier this week, CERT-UA confirmed our findings and publicly attributed the activity to UAC-0165, considered a subgroup of the outdated Sandworm APT. UAC-0165 targets are commonly observed in Ukrainian critical infrastructure, including telecommunications, energy, and government services.

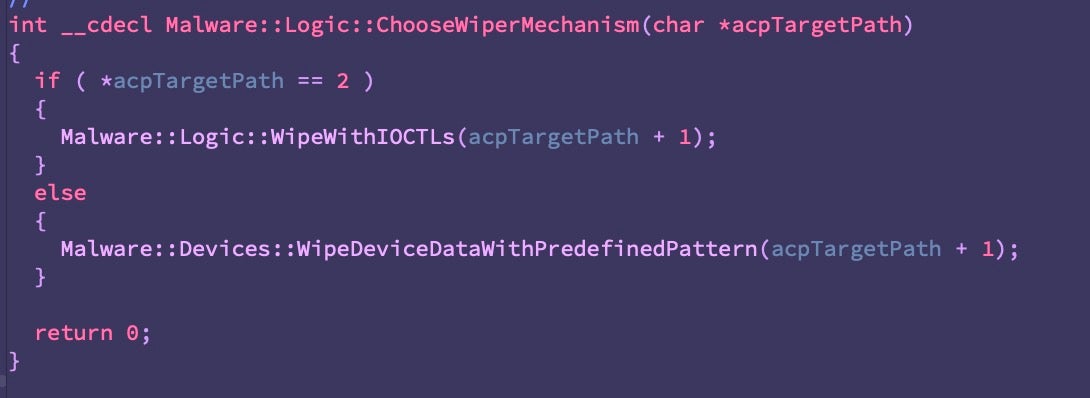

In September 2023, Ukraine SSSCIP publicly released a report on their latest findings of Russian linked threat activity. Notably, their section on UAC-0165 points to the continued use of GRU-linked, fake hacktivist personas as a medium for publicly announcing major intrusions and the leak of stolen data from Ukrainian victims.

On March 13th, the SolntsepekZ persona publicly claimed the intrusion into Ukrainian telecommunication organizations, three days prior to our discovery of AcidPour.

In addition to their Telegram presence, SolntsepekZ makes use of multiple domains under this persona. On Telegram, visitors are currently linked to solntsepek[.]com, which is associated with the hosting IP 185.61.137.155, of BlazingFast Hosting in Kiev. This hosting IP has previously hosted solntsepek[.]info as well as being related to solntsepek[.]org and similar to solntsepek[.]ru.

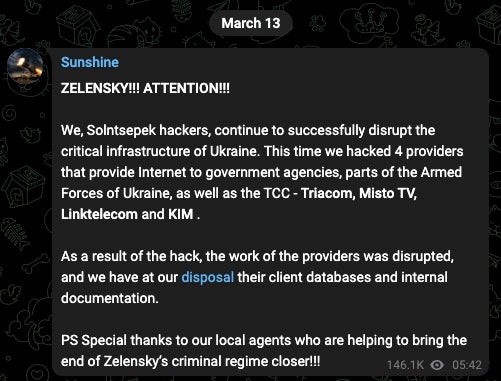

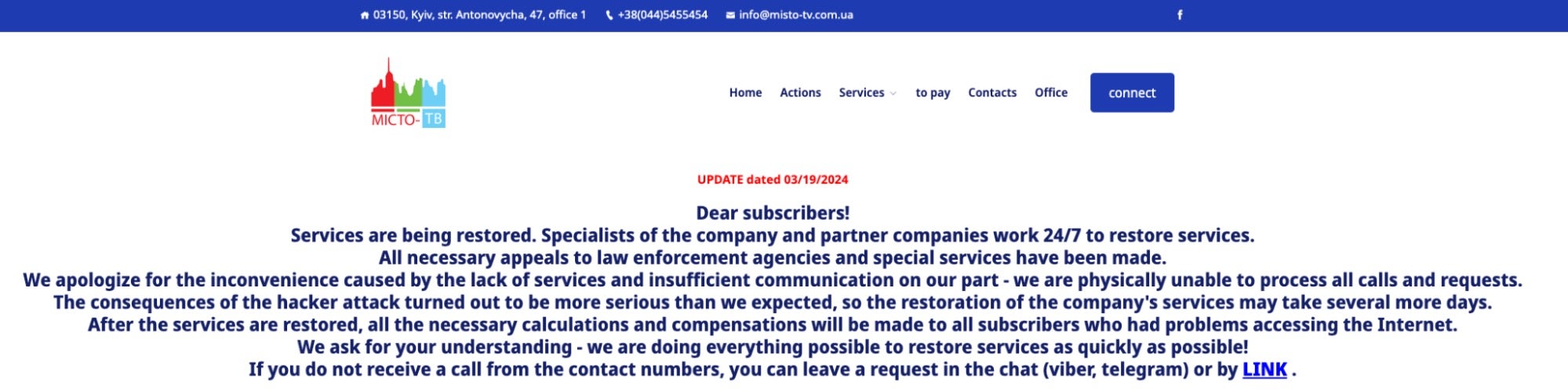

Review of the current state of these alleged target organizations indicates the impact is still ongoing. Below is an example notice currently on display from Triangulum, a group of companies providing telephone and Internet services under the Triacom brand, and Misto TV. Industry colleagues with Kentik are also observing this activity and have shared observations of the impact starting on March 13th as well.

At this time, we cannot confirm that AcidPour was used to disrupt these ISPs. The longevity of the disruption suggests a more complex attack than a simple DDoS or nuisance disruption. AcidPour, uploaded 3 days after this disruption started, would fit the bill for the requisite toolkit. If that’s the case, it could serve as another link between this hacktivist persona and specific GRU operations.

Conclusion

The discovery of AcidPour in-the-wild serves as a stark reminder that cyber support for this hot conflict continues to evolve two years after AcidRain. The threat actors involved are adept at orchestrating wide-ranging disruptions and have demonstrated their unwavering intent to do so by a variety of means.

The transition from AcidRain to AcidPour, with its expanded capabilities, underscores the strategic intent to inflict significant operational impact. This progression reveals not only a refinement in the technical capabilities of these threat actors but also their calculated approach to select targets that maximize follow-on effects, disrupting critical infrastructure and communications.

We continue to monitor these activities and hope the broader research community will continue to support this tracking with additional telemetry and analysis.